From the outset, the gallery’s programming leaned toward the socio-political, addressing issues rooted in the region while exploring broader questions of memory, identity, and the complex relationship between the Middle East and the West. Over time, a clear direction emerged, defined by singularity, and a deep commitment that drew the attention of collectors and art professionals alike, while fostering a “family” of artists united by a shared conceptual and critical space.

There was the generation of Walid Raad, Akram Zaatari, Marwan Rechmaoui, Wael Shawky, Taysir Batniji, Khalil Rabah, Yto Barrada and Rabih Mroué. There were also moments of renewed engagement with Arab modernism. Exhibitions dedicated to MARWAN, Etel Adnan, Aref el Rayess or Samia Halaby aligned with a growing interest among institutions and art historians in revisiting the region’s modernist legacy, one in which these artists now hold a central place. The gallery also turned its attention to a younger generation, including Lawrence Abu Hamdan, Mounira Al Solh, and Rayyane Tabet, and more recently artists like Dana Awartani, Alia Farid, Tarik Kiswanson, Sung Tieu, and Dineo Seshee Bopape.

With this evolving roster, Sfeir-Semler has largely contributed to promoting, in the Arab world, artistic forms such as video, photography, and performance—moving beyond the traditional categories of painting and sculpture. This commitment to conceptual art and to expanding the field of artistic practices is not surprising, considering the gallery’s early programming choices, with artists like Robert Barry and Ian Hamilton Finlay, or later, Hans Haacke.

Marking Sfeir-Semler’s 40th anniversary in Germany and 20th in Lebanon, The Shade unfolds at a particularly charged moment, when the tumult of global events is impossible to ignore. Traces of these realities resonate throughout the works on view, with most of the participating artists choosing to present recent works, never before shown in Beirut, that hold particular meaning for them today. Echoes of recent history surface in Wael Shawky’s Al Aqsa Park, a video centered on one of the most potent symbols of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict; in Rabih Mroué’s installation Again We Are Defeated, which grapples with the persistent violence across the region; and in Walid Raad’s Festival of Gratitude, a series of birthday cakes dedicated to dictators and tyrants like Saddam Hussein, Hafez al-Assad, and Recep Tayyip Erdoğan—gaudy confections drenched in color and cream.

Yet the exhibition also gestures toward possible worlds. Marwan Rechmaoui’s tree evokes themes of rebirth and childhood, while Dana Awartani’s large-scale installation from the series Come Let Me Heal Your Wounds, Let Me Mend Your Broken Bones reflects on the destruction of heritage sites through a poetic act of repair. Dineo Seshee Bopape’s landscapes draw on the postcolonial memory of South Africa, engaging with identity, resilience and renewal. In Tarik Kiswanson’s video, Ode to Joy – the anthem of Europe - is reinterpreted by children from immigrant communities in the Parisian suburbs. Khalil Rabah’s Olive Trees series offers a vital vision of hope and continuity. And there is of course the poetry in Etel Adnan’s landscapes, which have accompanied us for many years.

The title of the exhibition, The Shade, shrouds it in mystery. Shadows carry a wide range of symbolic meanings, shifting from one historical moment to another, from one culture to the next. They may suggest what is hidden or repressed, or what is investigated in secrecy. But here the reference draws from Carl Jung’s notion of the “shadow” as a space of untapped potential—an opportunity for transformation, where what has long been suppressed might finally emerge.

In Renaissance painting, shadows played a crucial role in sublimating light, serving as a fundamental element of visual composition to capture the world.

— Jean-Marc Prévost

Lawrence Abu Hamdan

b. 1985, Jordan

WshWsh (2025) is a series of kinetic sound sculptures inspired by the Ummayad fountains of Damascus. These fountains were placed at the entrances of mosques, at the intersections to the main ports of entry to the walled city, in hospitals and inside the private courtyards of the upper classes. While also used as water sources, air coolers and sites of ablution, these fountains were built during a time when land was scarce inside the medieval walled cities of Damascus and Aleppo. The white noise generated by each droplet falling from the spout to the pool, made it possible for people to live in these highly dense urban areas and block out the sounds around them. In Damascus fountains produced invisible walls of sound around their interlocutors. Away from prying ears all manner of negotiation could be conducted at their base. Under these umbrellas of white noise, weddings were arranged, elopings were plotted, business partnerships were formed, and hostile takeovers were hatched. All manner of communion and betrayal could be negotiated under this forcefield of sound.

Today surveillance is so pervasive that the white noise generated by a fountain is no longer capable of masking our chatter from outside ears. The fountain’s sound is too consistent and can easily be phased out by algorithms trained on its predictable behaviour. Enhancing and lifting out speech from recordings made in these former acoustic shadowlands can now happen at the click of a mouse. In order to restore their Ummayad era function, fountains would need to produce louder, more arrhythmic noises. Variegated sounds that would take advanced expertise just to catch a few of the words cloaked beneath it. These kinetic sculptures are trying to achieve just that. WshWsh is an attempt to modernise the social function of fountains in the era of mass surveillance.

water fountain, cymbals, 229 × 229 × 49 cm, unique

Walid Raad

b. 1967, Lebanon

A series of computer-generated birthday cakes and slices designed by Walid Raad for loved and/or detested 20th and 21st century global dictators, strong(wo)men, kings and queens, princes and princesses, emirs, sheikhs and sheikhas, sultans, popes, shahs, emperors and empresses, ayatollahs, presidents, prime-ministers, bosses, CEOs, and GOATs.

HD video, loop, color, silent, 12 seconds

Rayyane Tabet

b. 1983, Lebanon

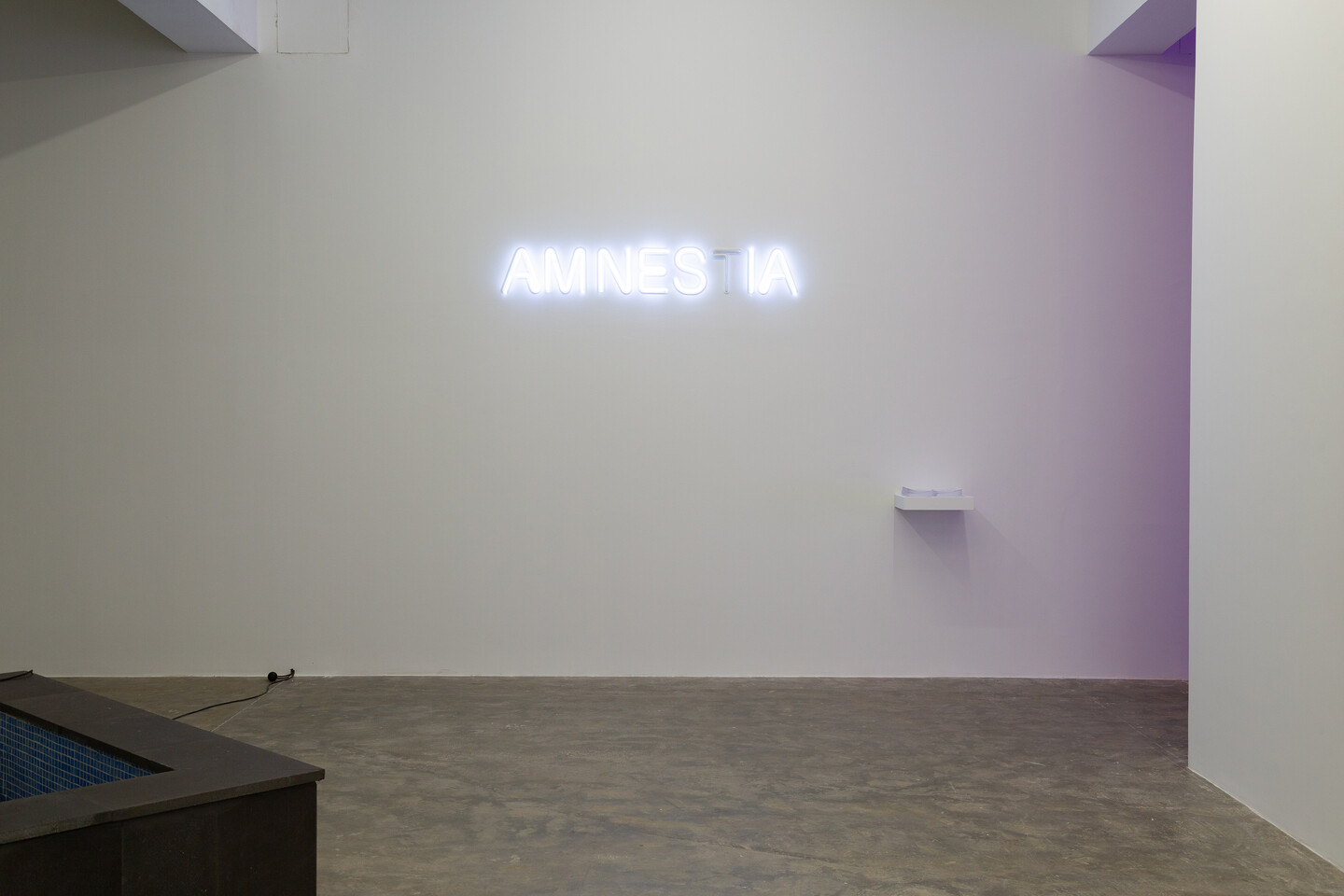

The Lebanese Civil War ended with a treaty that put into effect a general amnesty law which absolved all crimes committed before March 28, 1991.

Known as Law 84/91, this general amnesty turned out to be a ratification of the law that followed the civil unrest of 1958, which was a ratification of the amnesty that followed the civil conflict of 1860, which was a ratification of the amnesty that followed the communal tensions of 1845, which, in turn, was a ratification of the amnesty that followed the 1839 strife in Mount Lebanon.

Each one of these laws was enacted in an attempt to prevent future civil strife, but in essence, not only prescribed the wars to come but also contributed to centuries of impunity and prevented public recognition, restitution and reconciliation of the successive injuries enacted on people, places, and objects.

AMNES(T)IA is a neon by Rayyane Tabet that endlessly flickers between the words for Amnesty and Amnesia in Greek, a commentary on the endless cycle Lebanon and the world has been caught in for the last 200 years. Alongside the work is a pamphlet that reproduces the full text of the General Amnesty Law of 1991; a foundational text of contemporary Lebanon that is rarely published or discussed.

LED neon, white, 25 × 165 cm

Taysir Batniji

b. 1966, Palestine

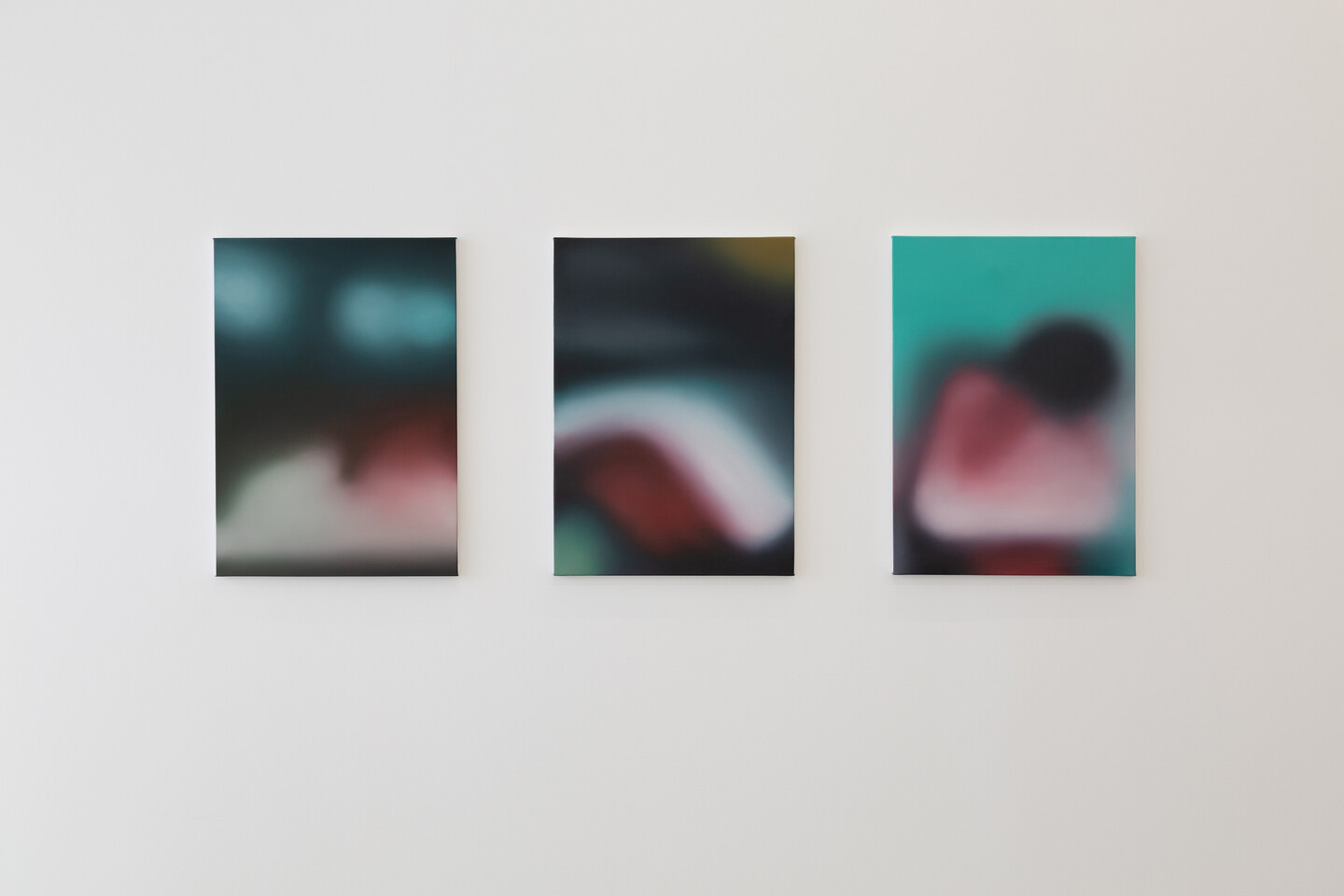

Based on Telegram news chat images, before their violent content fully downloads onto the screen of his phone, Remnants (2024-ongoing) are still-unseen photos that the artist meticulously paints. The process prolongs the moment of ignorance, resulting in almost serene, fluid works on canvas that suspend time, as if negating an unspeakable reality and preventing it from happening.

oil on canvas, 70 × 50 cm, each

Dana Awartani

b. 1987, Saudi Arabia

This work is a requiem for the historical and cultural sites that have been destroyed in the Arab world during wars and by acts of terror, and which expands with each iteration to make room for newer documentation. This edition adds testimony to the devastation in Gaza and the sites that have been flattened indiscriminately through bombings and bulldozers, alongside seven other Arab nations – Saudi Arabia, Syria, Tunisia, Libya, Iraq, Egypt, Palestine, Lebanon and Yemen.

Awartani tears nearly 400 holes across yards of silk, each rip marking a heritage site that has faced acts of terror and destruction. Then she darns—a fading practice far more intimate than patchwork but no longer valued—each gash tenderly as a gesture for healing; the scars a representation of the physical and emotional ones left behind in the real world. The fabric is dipped in around 50 herb and spice-based natural dyes that carry medicinal value, utilising the sacred healing properties embedded in traditional textile dyeing practices of Kerala, which Awartani spent time learning.

The panels, together, are borderless representations of annihilated cultural heritage. In the face of ongoing destruction as well as polluting effects of big industries, the work is both a plea to safeguard ancient civilisation in the Arab world as well as a bid to recall and rejoice in the collective history of artisanship, the knowledge of healing plants, and the venerable tradition of repairing and revering objects.

darned silk, 136 × 556 cm, unique

Yto Barrada

b. 1971, France

This new work by Yto Barrada is inspired by the song “Tiptoe Through the Tulips”, popularized in 1968 by Tiny Tim, also known as Herbert Butros Khaury, a singer of Lebanese descent. Singing of two lovers intruding into an abandoned field of tulips, the work is about trespassing into a space of liberty and encounters. Barrada evokes this vague terrain of tulips, once the symbol of the Ottoman Empire which colonized Lebanon and the region for over 600 years, and today a symbol of the intensive agriculture of tulips in the Netherlands. In Barrada’s work, the flowers are not only contained—they become the containers themselves, a subtle metalepsis of form, playfully constructed like building blocks, that turns the ephemeral petals into functional pieces.

cast aluminum and bronze, 22 × 11.5 × 8 cm, each

wood, paint, c.a. 22.5 × 13.5 × 6.75 sm, each, unique

Marwan Rechmaoui

b. 1964, Lebanon

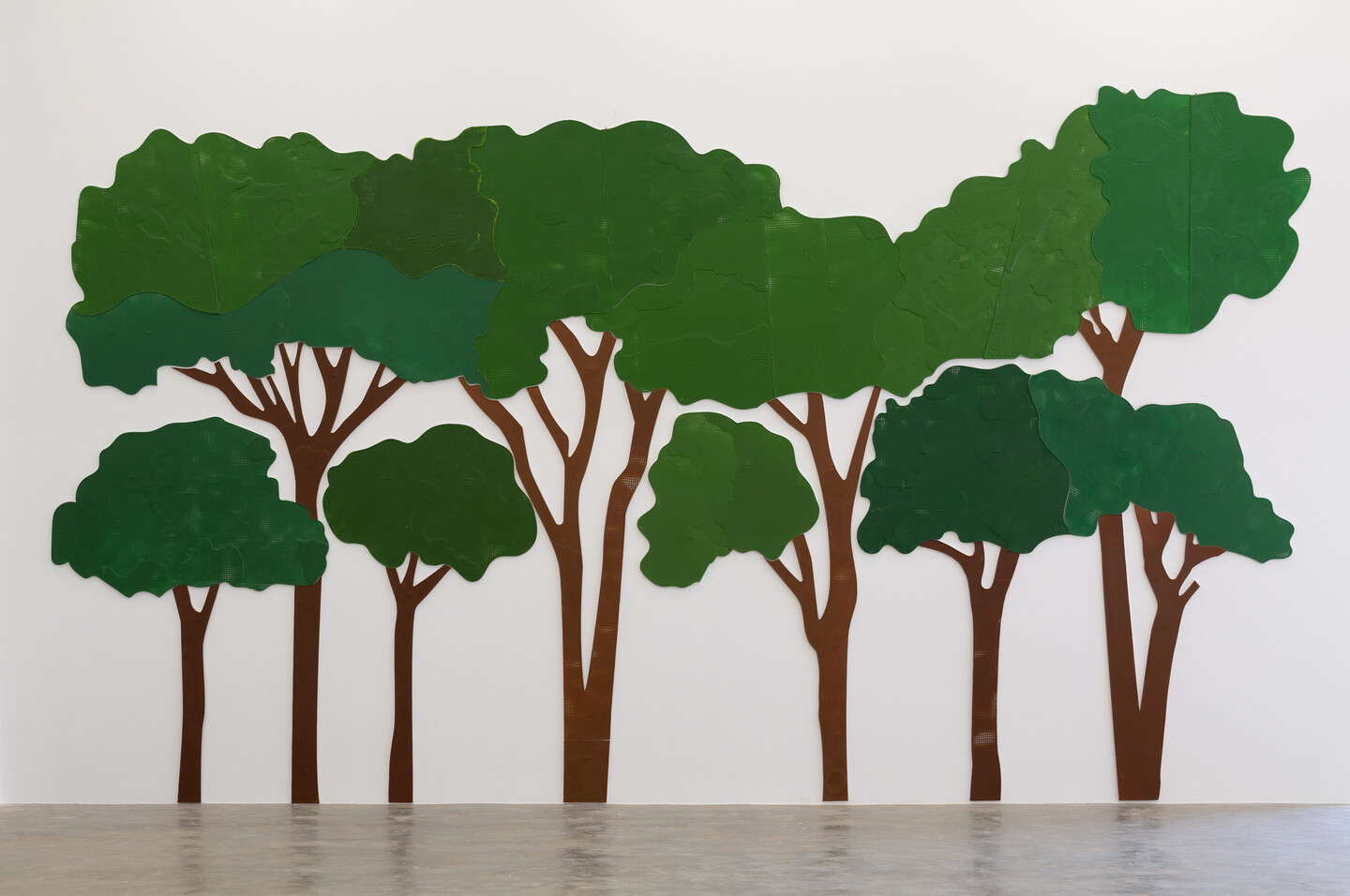

Marwan Rechmaoui’s forest responds to an essay by John Berger, in which the author recounts a conversation with his own mother. The two were talking about the disturbance caused by a dog that was furiously barking; its chain was too short to allow it to reach the shade. Berger’s mother suggested that simply lengthening the chain a little would allow the distressed animal to find shade, calm down, and that consequently many good things might flow from this small act.

oil paint, beeswax on aluminium, 300 × 500 cm, unique

Mounira Al Solh

b. 1978, Lebanon

The Murex shell was discovered by the dog of Melqart, as he walked on the beach in Tyre, Lebanon. He bit on the shell, and as a result looked like he was bleeding from his mouth. Upon looking more carefully, Melqart discovered that it was not blood, but the snail inside the Murex shell made it look so. According to the myth, a nymph asked Melqart to make her a dress with that color.

The dye was greatly prized in antiquity because the color did not easily fade, but instead became brighter with weathering and sunlight. The Phoenicians created outside of their cities sites where they would capture and process the shell to colour fabrics with it. Thousands of shells were needed to color dye just a few centimeters of that highly prized Tyrian red. It is said that it smelled like garlic, even after washing it. Al Solh’s textile shows a hand-embroidered Murex shell that morphs into an abstract shape, mixed with found threads and organic fibers.

embroidered textile, 159.1 × 151 cm, unique

Khalil Rabah

b. 1961, Palestine

From his home in Ramallah, Palestine, Khalil Rabah found a means of confronting daily life through the repeated act of drawing olive tree trunks. Symbolic of Palestine, these trees are regularly cut down and uprooted. In Rabah’s work the fragments, painted on paper with bright colors, almost become severed body parts.

oil pastel on Daler-Rowney fine grain - heavyweight paper, 42 × 60 cm, each

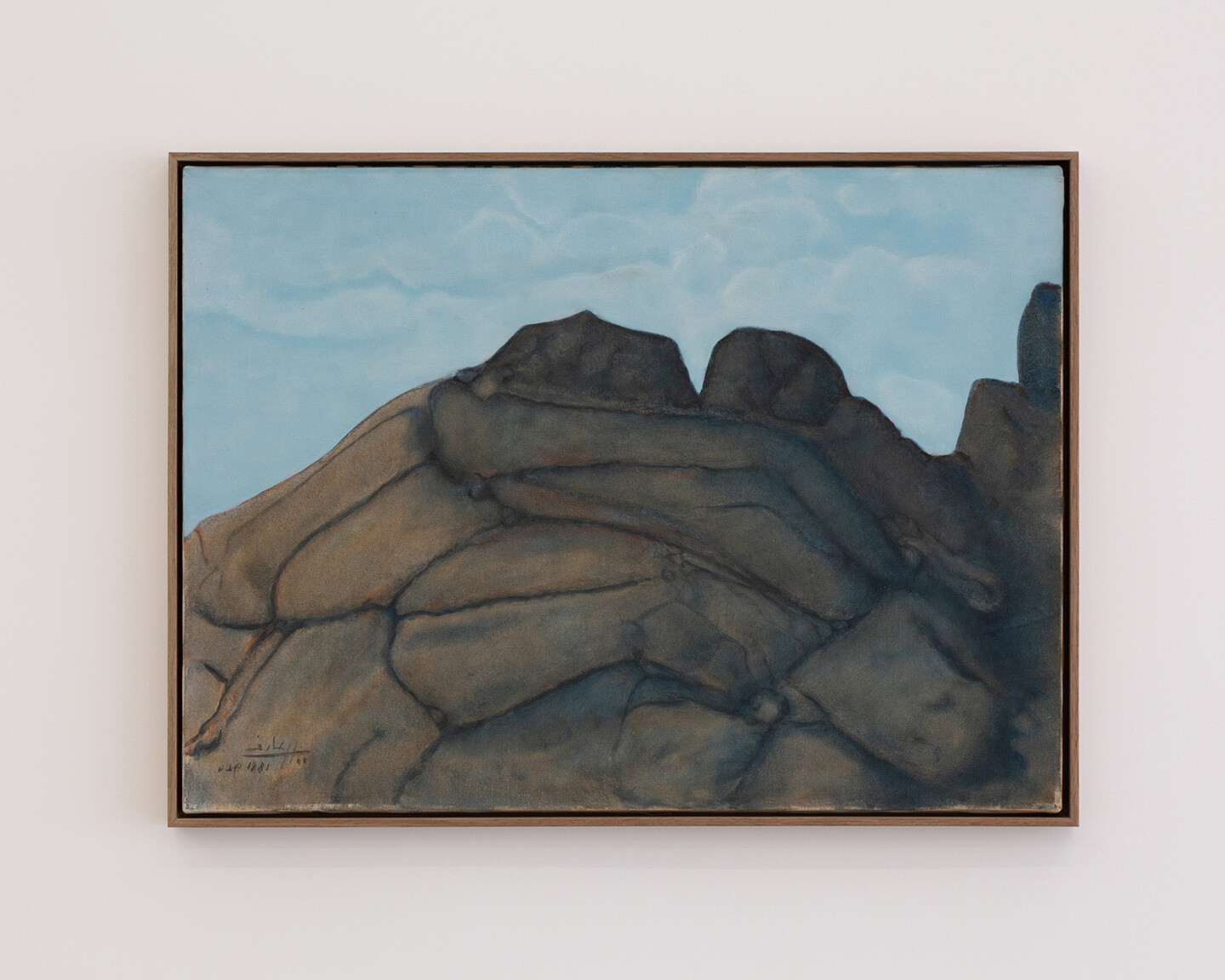

Aref El Rayess

b. 1928, Lebanon - d. 2005, Lebanon

Aref el Rayess spent the best part of the 1980s in Saudi Arabia. Initially commissioned to create large-scale public sculptures in Jeddah, Tabuk and Riyadh, he was also an advisor to the Jeddah Open Air Museum. For several years, faced with the landscapes of Saudi, he painted deserts, repeatedly, compulsively, an almost mystical, meditative exercise that turned dry lands into abstract, sculptural, color fields. The works on view are key in the series, showing desert stones piled up into imaginary constructions.

oil on canvas, 55 × 76 cm

oil on canvas, 58 × 73 cm

oil on canvas, 58 × 79 cm

MARWAN

b. 1934, Syria - d. 2016, Germany

Producing sketches, watercolor drawings, etchings or paintings, MARWAN developed his Sisyphean painterly language through a meditative, spiritual approach by painting over and over the same face, often on the same surface. The works on view are watercolors from the 60s to the 80s, that follow the shift in his representation of the human figure. Moving from a full body representation over time, he starts to focus solely on the human face in the early 70s, painting the human visage as a landscape. Over the years, they morphed into what he called “heads”. Abstract brushstrokes in earthly tones at first glance, they reveal themselves as multiple melancholic faces, layered one on top of the other.

watercolor on paper, 51.6 × 67.6 cm

watercolor and graphite on paper, 41.7 × 30 cm

Etel Adnan

b. 1925, Lebanon - d. 2021, France

Ever since encountering La Dame à la Licorne, the sixteenth-century tapestry series at the Musée de Cluny in Paris in 1949, Etel Adnan has been interested in making tapestries. She started producing small drawings, or “drafts”, specifically intended to become larger works, weaved as tapestries or even produced as ceramic murals at a larger scale. In the mid-60s, on her way from the United States to Egypt, she stopped in Tunisia where she met a master weaver and commissioned her very first two tapestries from those drafts. Since the 2010s, Adnan’s tapestries are handwoven in France at Les Ateliers Pinton d’Aubusson (Felletin).

wool tapestry, synthetic dyes, handwoven by Les Ateliers Pinton d’Aubusson-felletin, France, 200 × 162 cm

Sung Tieu,

b. 1987, Vietnam

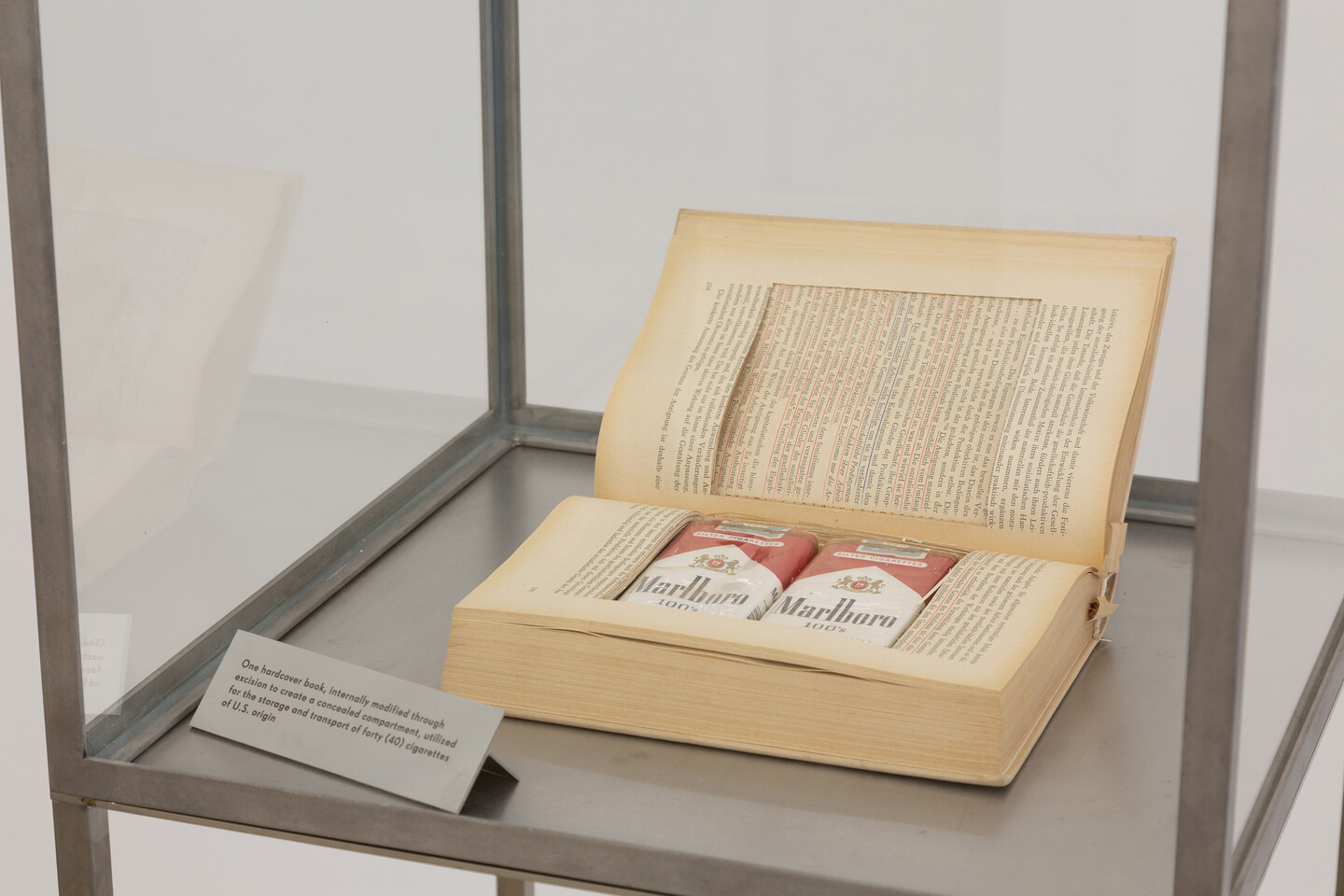

Sung Tieu’s artistic practice examines the tensions between individual lived experiences and the overarching mechanisms of systemic regulation, offering a critical perspective on Germany’s divided history particularly of the 1980 recruitment agreement between the German Democratic Republic (GDR) and the Socialist Republic of Vietnam. This agreement resulted in the migration of around 60,000 Vietnamese contract workers to the GDR during the 1980s. The works shift focus to the far-reaching consequences of the collapse of the GDR, depicting its ongoing impact on the identities, roles and social networks of the Vietnamese community in Germany, often explored through the practice of smuggling. While the various objects on view might at first glance be difficult to identify, they turn out to be products made by Vietnamese contract workers in Germany. The actual objects, which don’t carry any trace of this history, were made by some of the approximately 70,000 workers, who came to the GDR between 1980 and 1989. Like the objects, these workers have been erased from the cultural and social landscape of the time.

book, American cigarettes, perspex, stainless steel, glass, 151 × 41 × 41 cm

silk screen on stainless steel, screws, washers ,18 parts, 29.7 × 534.6 × 0.2 cm

Photographic documents produced by Walid Raad from Algeria to Iran, Turkey to Yemen.

pigmented inkjet prints, 31 × 61 cm, each

Tarik Kiswanson

b. 1986, Sweden

Tarik Kiswanson’s latest video work unfolds within the Conservatoire de Saint-Denis, situated in the northern suburbs of Paris. The conservatory was established in 1977 as a social project to offer music education to children and adults in the underprivileged and multicultural city. Over time, it has evolved into a comprehensive cultural institution, providing lessons in a wide range of musical disciplines. The film quietly observes the hands of three local children—aged 8, 10, and 11—as they grapple with the task of deciphering the score of the Anthem of Europe, commonly known as Ode to Joy, drawn from the final movement of Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony. Through the children’s hands the partition is deconstructed, rewritten and reimagined.

color, sound, upright 16:9 flatscreen, 16 minutes 20 seconds

Alia Farid

b. 1985, Kuwait

Commissioned by Sharjah Art Foundation, Alia Farid’s recent work explores the material impact of oil extraction in the Arab Gulf through two predominant materials; blue faience, an aqua glaze that dates back 6000 years, and polyester resin, a byproduct of petroleum production that originated in the 20th century. This work, from a series of six plates commissioned for Sharjah Biennial 16, builds on research conducted in Stanford University into thousands of Iraqi objects and records withheld in the US. The work encompasses the artist’s ongoing experiments with a type of resin manufactured by United Oil Projects called Kupol LR 3303 which she layers with images tracing her matriarchal lineage as well as Iraqi spiritual traditions that assume the form of charts and cosmological maps.

two resin panels, fibre glass and polyester resin (Kupol LR 3303 manufactured by United Oil Projects Company, Kuwait), photocopy paper, ink, stainless steel bolts, 243 × 183 × 15 cm, each, unique

Akram Zaatari

b. 1966, Lebanon

In 2022, Zaatari used a photograph of a nude woman—likely a sex worker—who had posed for her physician Farid Haddad in the 1920s or 1930s. Originally printed on a transparency to be projected onto canvas and turned into a painting, the image had served only as an intermediary tool. Zaatari reworked it into a new artwork: an iconic bas-relief that narrates the photograph’s story while distancing it from its photographic form. The intention was to conceal the woman’s identity while honoring her presence, naming her the Venus of Beirut and granting permanence to what was meant to remain unseen.

3D routed, hand-polished Grey Bardiglio imperial, 50.5 × 50.5 × 4 cm

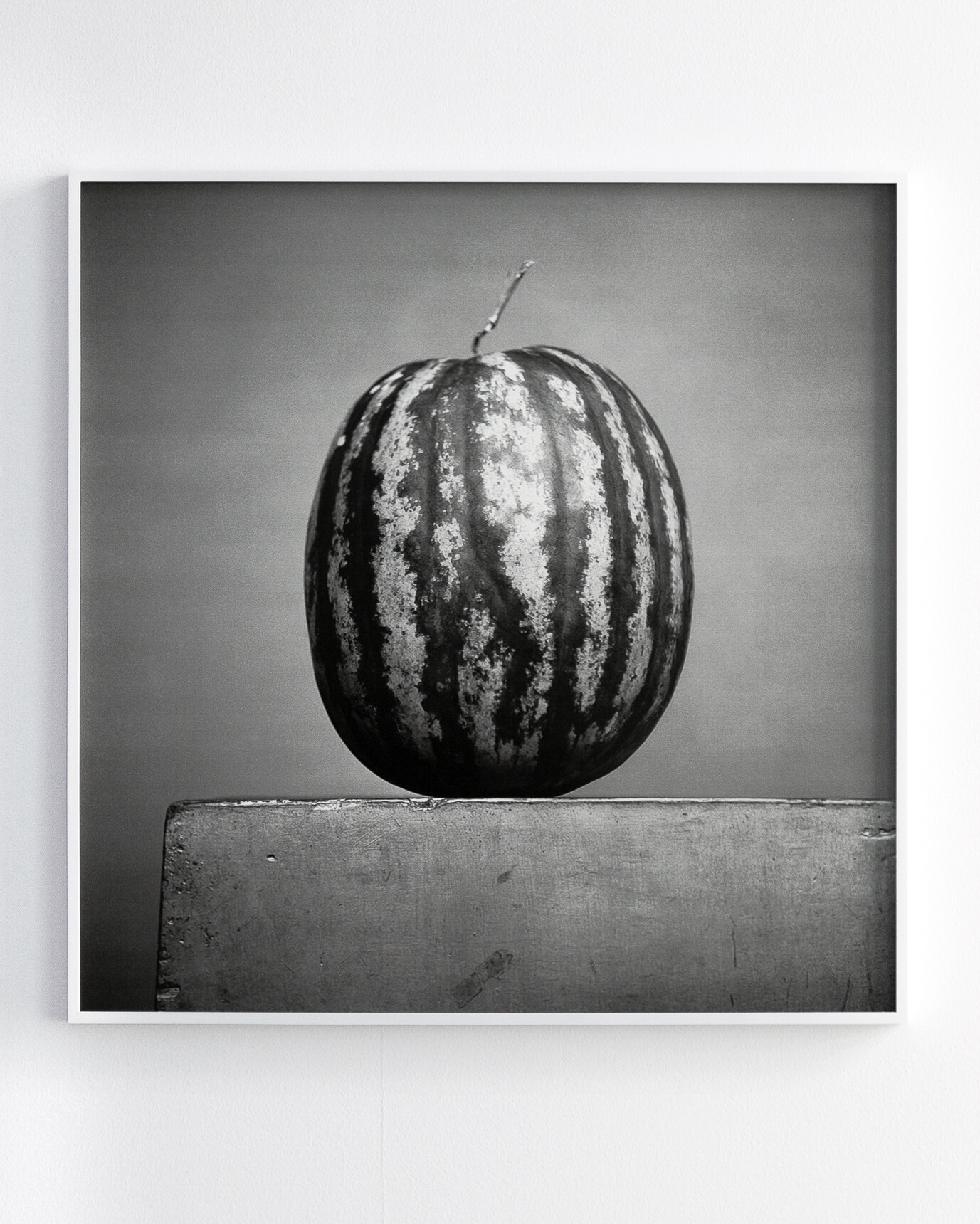

Around 1970, a farmer brought an unusually large watermelon to Studio Shehrazade in Saida, asking that it be photographed as a record of his production before it got sold. While the photo initially served a simple documentary purpose—perhaps also fulfilling a self-congratulatory impulse—it takes on broader significance nearly fifty years later, namely for something it did not intend. The watermelon has, since, become an unofficial symbol of Palestine; its colors echoing those of the Palestinian flag, often banned or censored. In this context, the photograph’s muted colors come to evoke the broader suppression of Palestine’s emergence and national expression.

black and white silver print, 90 × 90 cm

Rabih Mroué

b. 1967, Lebanon

Mroué plays with images, overlapping silhouettes through a projection on prints, to highlight the repeated cycles of violence affecting people in the Middle East. By examining his own encounters with the conflict as mediated through the news, the artist serially tracks the recurring impressions of conflict. The works create an homage to the phantom presence of the dead.

112 printed drawings, video, sound, loop, 210 × 336 cm

Wael Shawky

b. 1971, Egypt

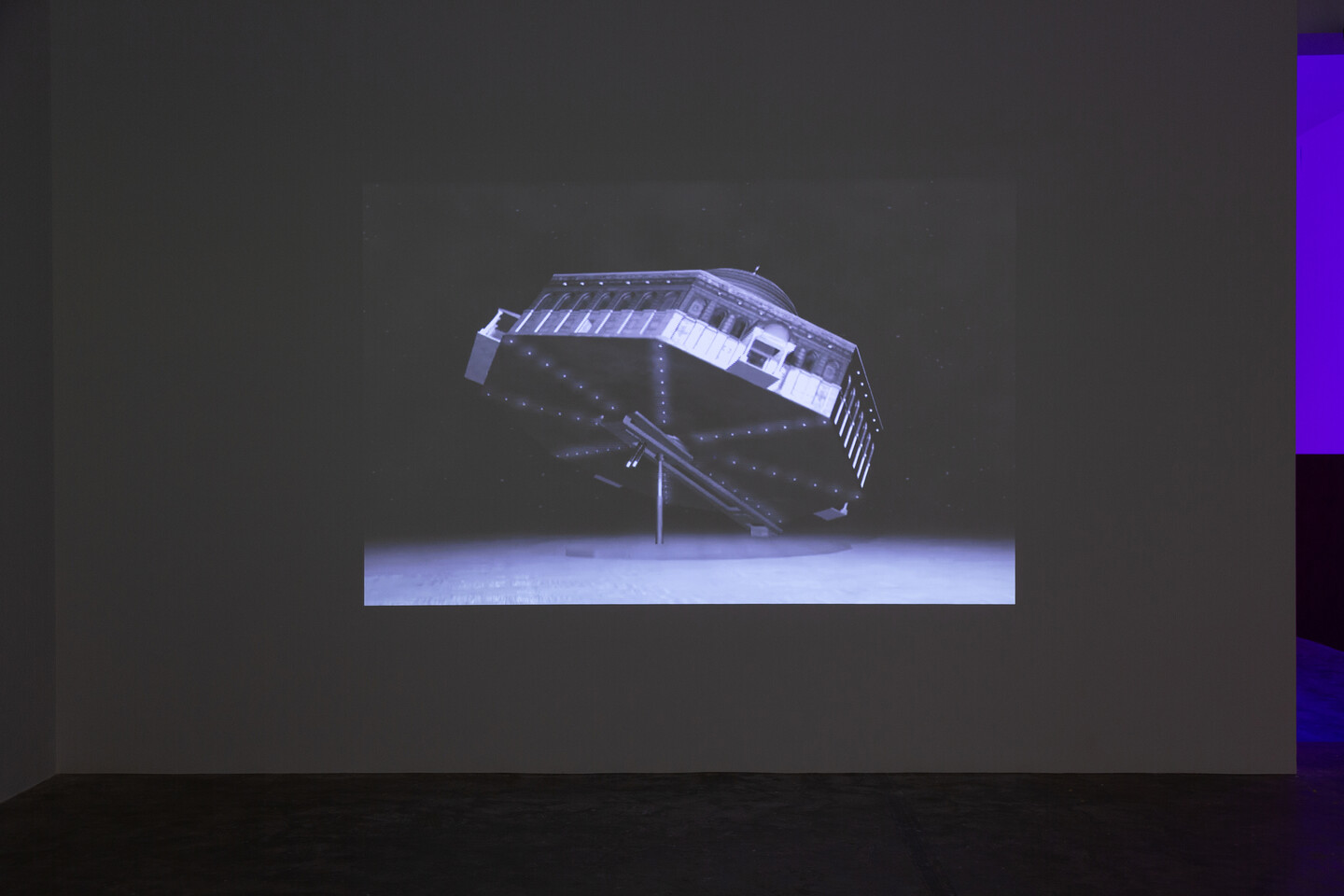

Al Aqsa Park (2006) is an animated film installation where the Dome of the Rock, the symbolic referring to the Al-Aqsa complex in Jerusalem, is displayed as a fairground carousel. Although the work brings an additional reflection on the intersection of the discourses of political systems and religiosity, the Al-Aqsa Park installation is essentially centered on the idea of controlled entertainment that the experience of riding a carousel, as well as its spectacle, delivers. The carousel, conventionally the center-piece of a fair, circling at a speed to generate weightlessness and ‘freedom’, is actually a machine maneuvered by an operator, according to a tightly controlled schedule.

Al-Aqsa Mosque is the third most important mosque in Islam after al Masjid al-Haram (The Sacred Mosque) in Mecca then Al-Masjid al-Nabawi (The Prophet’s Mosque) in Medina.

video animation, black and white, sound, 3:4, 10 minutes loop

Dineo Seshee Bopape

b. 1981, South Africa

Dineo Seshee Raisibe Bopape invites us to smell, taste, hear, see, feel, walk, sit and dream. In dreaming, the artist explores the connections between the suppressed and fragmented parts of material form, life and the self.

Bopape immerses herself in the world of dreams, forests, land, water and stories of African rainmakers. It has been a practice of various indigenous cultures globally to administer and receive healing through dreams, in this process engaging various plant life forms. Soil is one of the recurring matters in the exhibition, as a repository of the universe’s memories and potential and as a record of social, historical and political stirrings; a symbol of our collective connection to the nurturing essence of the dreaming Earth. Site-specific and sourced locally for each iteration of the installation, the organic material she uses become a symbol of our collective connection to the nurturing essence of the dreaming Earth.

multimedia installation, various dimensions, unique