“Another exhibition at another foreboding historical moment” says the invitation card to Walid Raad’s exhibitions at Sfeir-Semler galleries in Karantina and Downtown. Raad’s artworks have time and again engaged such moments and what they make evident, possible, probable, thinkable, sayable, and imaginable. He has done so via three long-term ongoing projects: The Atlas Group (1989-2004), Scratching on things I could disavow, and Sweet Talk: Commissions (Beirut).

In this exhibition in Beirut, Raad once again displays documents that he creates but that he relates to as found and/or received, and attributes, in many instances, to imaginary collaborators. The documents are presented as aesthetic objects along with their accompanying stories. Raad’s objects are photographs (or most often, photographs of other documents, be they notebooks, paintings, drawings, maps), videos, sculptures or mixed-media installations. His stories are short. They read like reports, transcriptions of stories recorded by Raad, and often attributed to imaginary characters such as Suha Traboulsi, Farid Sarroukh, and Manal B. Tarabay. Raad relates to these characters “less as fictional creations and more as artistic collaborators who dwell in another realm, occasionally sending me signals I am able to decipher.

The dual exhibitions at Sfeir-Semler in Beirut showcase new and recent works. In Karantina, two large-scale immersive video installations fill entire rooms, enveloping viewers in trance-inducing images. These are accompanied by four sculptural works, and five series of prints that are typical of Raad’s approach, with his Dada-esque twist on current events.

single channel projection, black and whitem silent, paper figures, 00:39:22, loop, Ed. 1 + 1 AP

singel channel projection, clach and white, silent, paper figures, 00:39:22, loop, Ed. 1 + 1 AP

singel channel projection, black and white, silent, paper figures, 00:39:22, loop, Ed. 1 + 1 AP

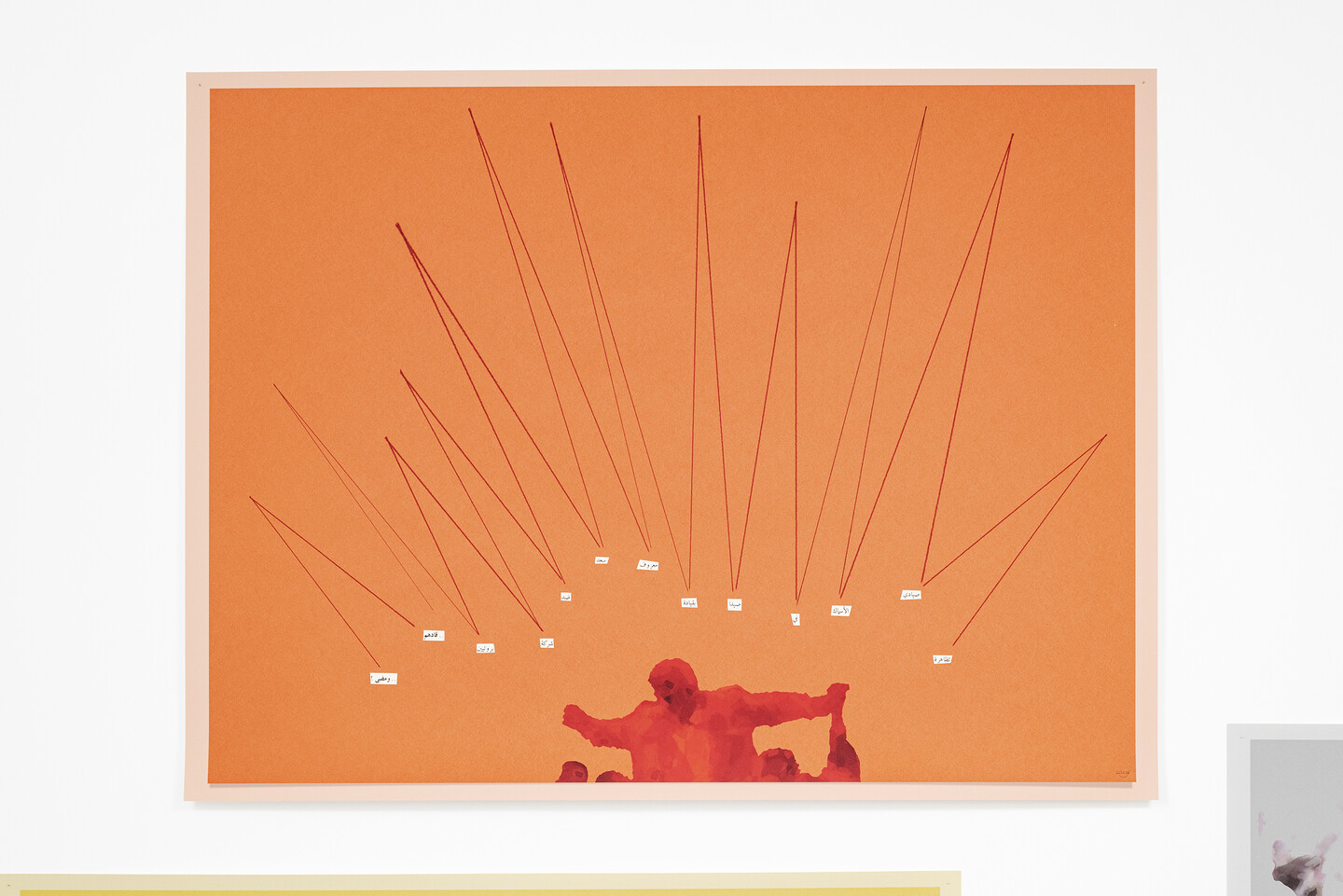

The 15 prints in Festival of (In)gratitude for example, look at first glance like large colorful abstractions, but upon closer inspection, they reveal familiar media images and newspaper fragments, turning journalistic captions into disjointed word salads. Similarly, a somewhat banal yet colorful book of World War I uniforms becomes on closer inspection an index of Lebanese artists collaborating with warlords. Raad’s works reveal obsessive detail: small, painstakingly cut black and white portraits of military or political figures; cutout newspaper captions in Arabic and English; drawn notations; photocopied maps, layers of stacked, organized paperwork. His stories are displayed in wall-texts that appear alternately as captions and institutional descriptions. But in Raad’s work, the stories are part and parcel—visual and conceptual elements that both anchor and wrest the displayed photographs, sculptures, and videos in and from their historical origins.

pigmented inkjet print, 152.4 × 203.2 cm, Ed. 1 + 1 AP

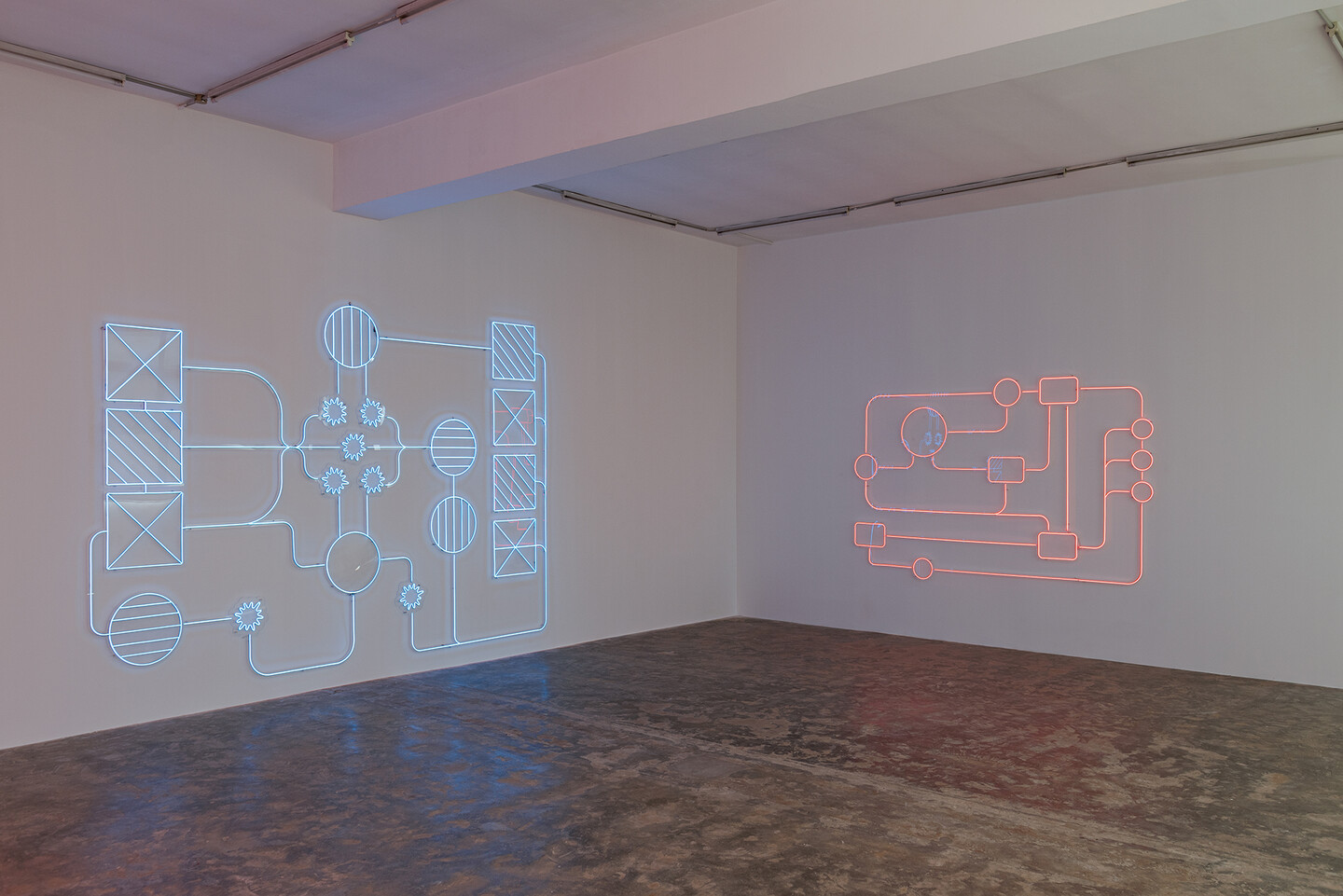

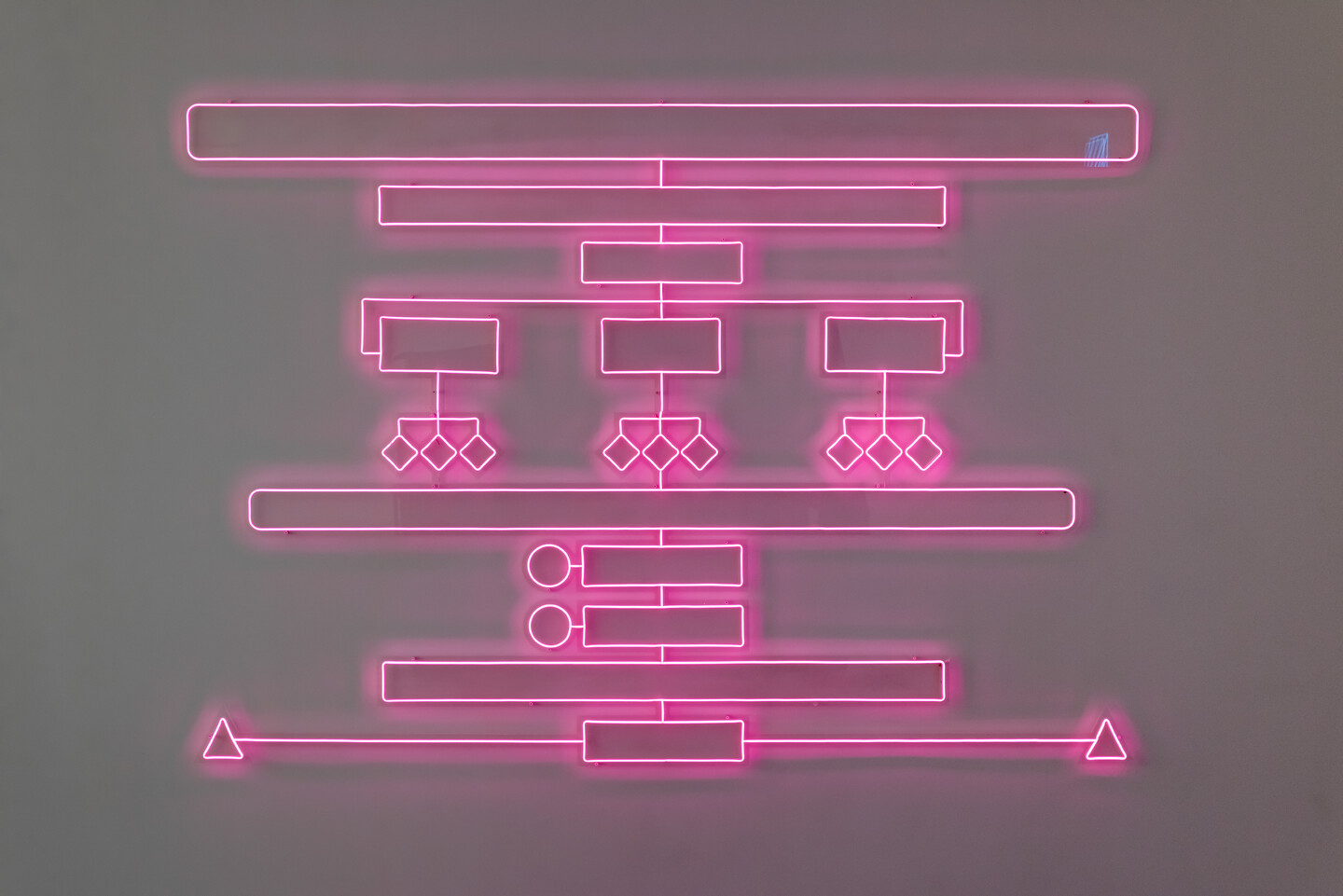

In September 2019, Lebanon’s Ministry of Finance commissioned three graphic panels to accompany its investigators’ upcoming presentations to the International Criminal Court (ICC), the International Monetary Fund (IMF), and the U.S. Treasury Department. The task fell to a junior law clerk, a self-described “part-time derivative artist,” Manal B. Tarabay.

Unsurprisingly, her panels sat uncollected in Neon International ’s depots in Fanar where I found and purchased them in 2023.

LED neon, 294.57 × 191.02 cm, unique

The yellow envelope and its contents were donated by Anonymous to The Atlas Group in 2003. The donation was accompanied by the following note:

At 17, and as a budding photographer, I was asked by a cousin who owned my favorite Beirut patisserie to take pictures of his cakes. I did so gladly, hoping to be compensated with the eclairs and tarts I fancied there.

After weeks on the job, I came to realize that this patisserie was also the favorite of Lebanon’s warlords and politicians. I came to this conclusion when I organized the order dates and first names on the cakes and then realized they coincided with the warlords’ birthdays: October 25 and “Samir,” for Samir Geagea; January 22 and “Amine,” for Amine Gemayel; August 7 and “Walid,” for Walid Jumblatt; September 7 and “Omar,” for Omar Karami, and so on.

Weeks later, I started to fantasize about poisoning the cakes.

But unfortunately (or fortunately), I was let go before I could implement my plan because my staging and photographic skills were clearly not up to par.

pigmented inkjet print, 42 × 59.5 cm, Ed. 5 + 2 AP

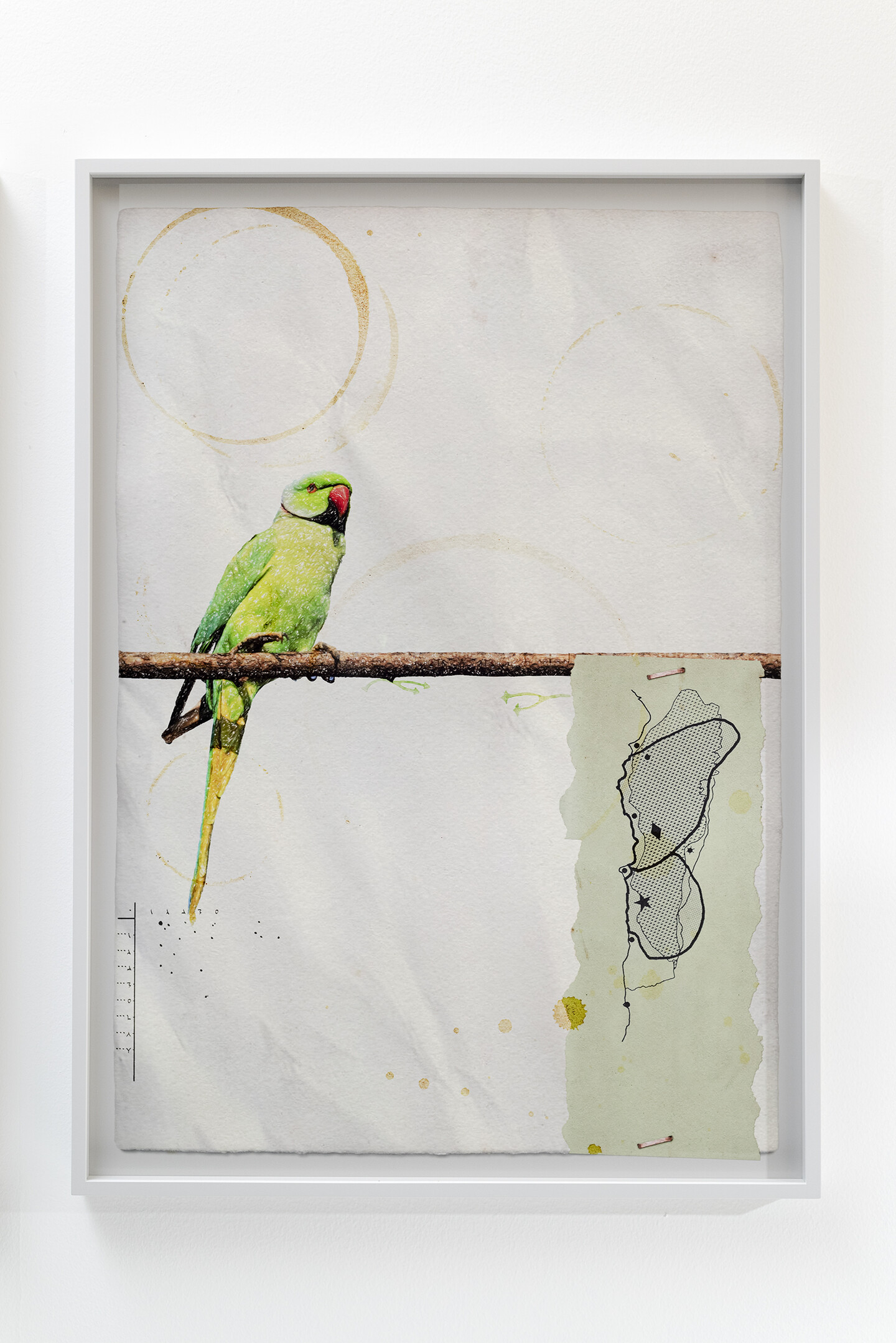

The following pages were donated anonymously to The Atlas Group in 1997. A three-year research project yielded the following conclusion:

In 1981, a left-wing militia bred various species of invasive birds. Their aim was to send the birds into its enemies’ territories to decimate that ecosystem. The unit in charge of this operation kept detailed notes on all the birds they raised, and to which parts of Lebanon they were sent.

The invasive bird strategy was a complete failure, and was abandoned after seven runs.

pigmented inkjet print, 84 × 60.5 cm, Ed. 5 + 2 AP

pigmented inkjet print, 84 × 60.5 cm, Ed. 5 + 2 AP

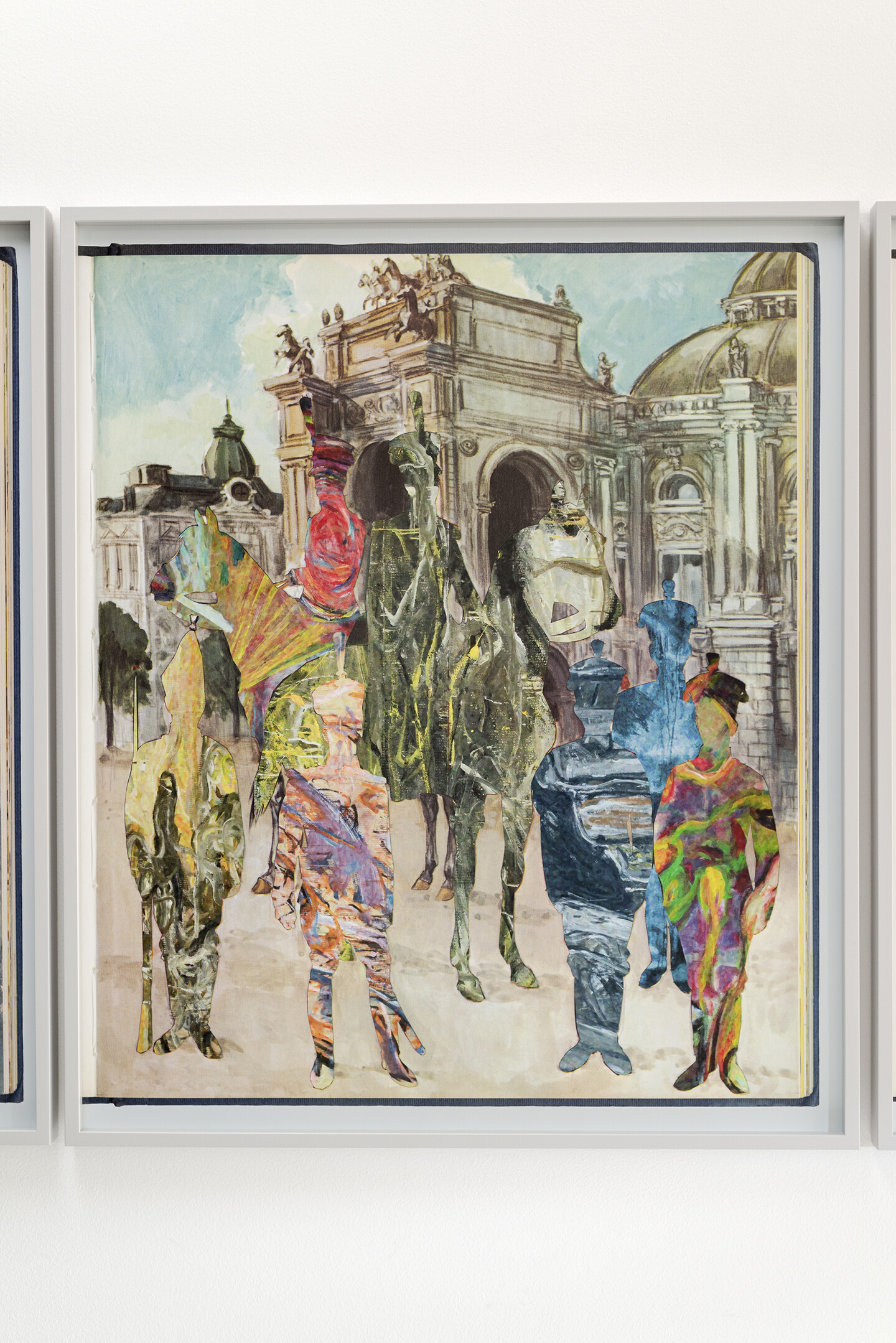

In 1976, most public monuments in Beirut were hastily disassembled and stored in unmarked crates to protect them during the ongoing wars. The crates were also dispersed to various secure storage sites.

In 1993, the crates were gathered in the hope of reassembling the monuments. However, the absence of any breakdown notation or reassembly protocol resulted in the odd composition of new monuments, one of which is on display here.

pigmented inkjet print, 90 × 76 cm, ED 5 + 2 AP

pigmented inkjet print, 90 × 76 cm, Ed. 5 + 2 AP

Several Lebanese artists volunteered their services during the war years and created camouflage military fatigues for the numerous fighting militias. Their designs were catalogued in this book by Farid Sarroukh, an immodest painter who was irked at not having been asked to submit his own designs.

wood, 378 × 289 × 100 cm

Beginning in the mid-1990s, hundreds of buildings in downtown Beirut were demolished, their rubble dumped in the sea in efforts to rebuild the new post-war city center.

The works displayed here derive from dozens of implosion videos recorded by aggravated former tenants who had been ousted and/or bought off to make room for the new downtown.

multi-channel video, color, silent, 05:10:00, loop, Ed. 5 + 2 AP

For 30 years, Raad has been making his own documents. Most of the time, his documents allude to events that unfolded in Lebanon during the past five decades. And while these events did indeed unfold, they did so “not in this historical world but in another realm, one with its own strange landscape and odd characters,” says Raad. His artworks are his attempts to visualize and narrate what he sees and hears there.