Sfeir-Semler gallery presents Walid Raad’s fifth solo exhibition in our Hamburg gallery. The New-York based artist focuses on events, images and stories made possible by the Lebanese wars of the past few decades. Blithely blurring the lines between the historical and the imaginary, Raad’s works engage how experiences of extreme violence are lived and experienced, as well as the effects of violence on bodies, minds, art and tradition.

Born and raised in Lebanon, the artist continues to explore the Lebanese wars through The Atlas Group (1989-2004), an ongoing art project that takes the form of an (imaginary) archive. With this project, Raad usually leans on historical events and creates imaginary documents that he then attributes to imaginary and historical figures.

I might die before I get a rifle, 2018

Attributed date: 1993

Attributed to: Hannah Mrad

In 1991, and after 14 years in the Lebanese Communist Party, Hannah Mrad was recruited into the Lebanese Army’s Ammunition and Explosives division. Months into his new assignment, he found himself unable to remember the names of the thousands of explosive devices he was meant to master. He began to photograph them, to enlarge them, hoping that his human-sized photographs would aid his memory. They didn’t and he was let go.

pigmented inkjet prints, 160 × 212 cm each, Ed. 7 + 2 AP

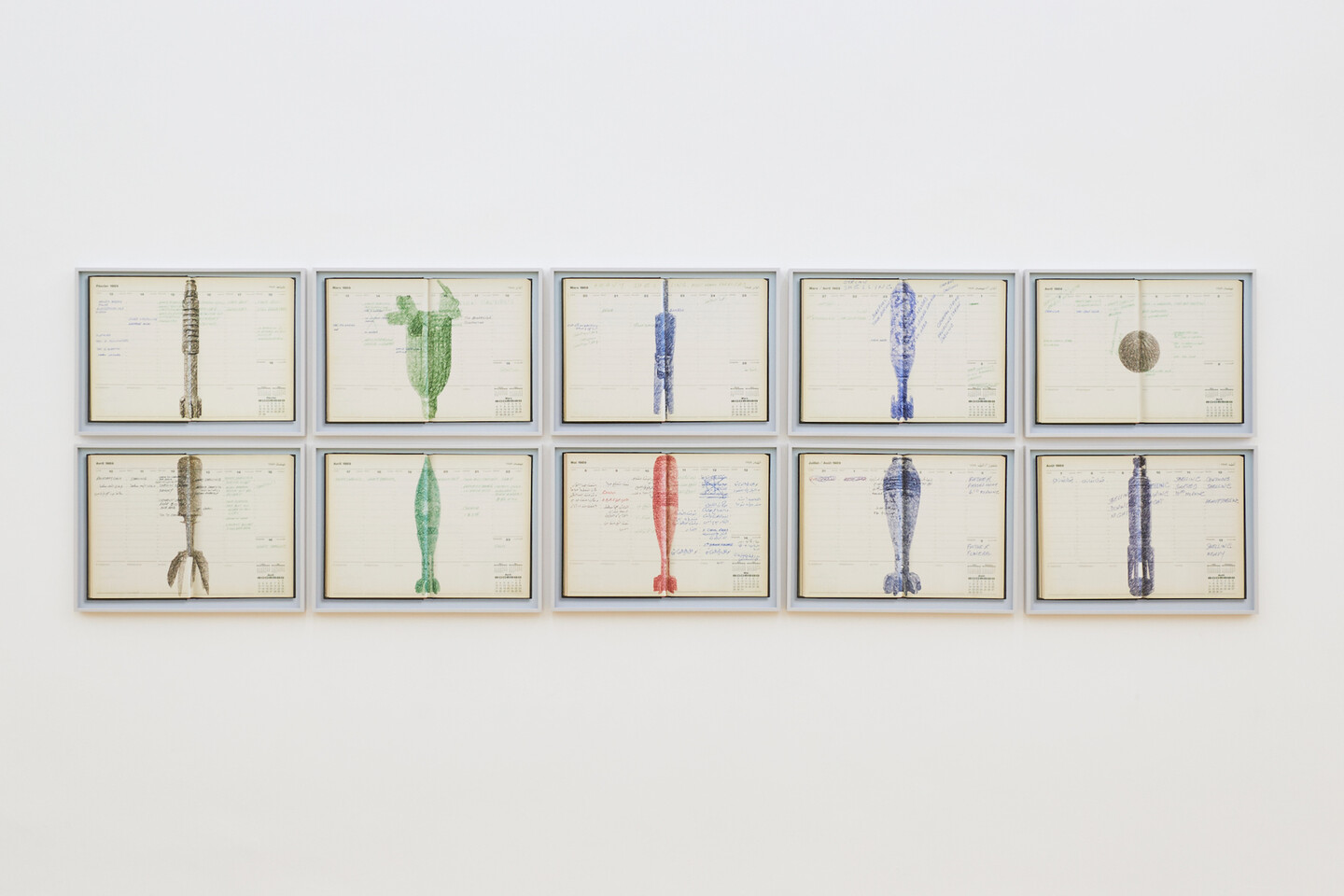

I want to be able to welcome my father in my house again, for example, shows pages from a 1989 diary, which is attributed to the artist’s father. Each page includes a drawing of a shell that fell around his house that year, and notes from daily life written under the bomb drawings (the devaluation of the Lebanese pound, the prices of building materials, the lack of gas...). Here, Raad proceeds from his father’s actual diary to create that diary’s twin, an imaginary document that condenses into a single spread the historical, economic, as well as the aesthetic qualities of the experiences of war.

I want to be able to welcome my father in my house again, 2018

Attributed date: 1993

Attributed to: Ghanem Mansour Raad

Throughout the war years, my father kept a diary in which he detailed the Lebanese pound's free fall, the price of construction materials, and the kinds of bombs that fell around his home.

pigmented inkjet prints, 50 × 64.6 cm (each), Ed. 5 + 2 AP

In another artwork titled Better be watching the clouds and attributed to a retired army officer, Raad catalogues the various local, regional and international leaders that have shaped Lebanon’s recent political and military life. They are portrayed through the code names given to these leaders by Lebanon’s security services. Or so Raad says.

Better be watching the clouds, 2017

Attributed date: 1992

Attributed to: Fadwa Hassoun

The following plates were donated in 1992 to The Atlas Group by Fadwa Hassoun, a retired officer in the Lebanese Army. Throughout the 1970s and 1980s, Lebanon’s Deuxième Bureau code-named local and international political and military leaders in the language of local flora. As a trained botanist, Hassoun’s job was to assign the code names to the leaders. Hassoun kept track of all code names in a logbook where she collaged faces of the leaders onto flowers and trees. The plant’s name became the politician’s code name. As such, Hosni Mubarak became Dwarf Mallow; Mikhail Gorbachev, Purple Carline; Ronald Reagan, Kermes Oak; And Kamal Joumblatt, Pink Sorrell.

76.2 × 50.8 cm each

inkjet prints, 76.2 × 50.8 cm each

The exhibition also presents Raad's ongoing project Scratching on things I could disavow which probes the art history of the Arab World. This project was initiated in the early 2000s, when the building of new infrastructures for the arts was accelerating in the region, and looks at how artworks anticipate and respond to the historical events they witness. Letters to the reader suggests that certain artworks on display in the fictitious Museum of Modern Arab Art in Beirut have somehow lost their shadows. Wondering whether these had been destroyed or lost, the artist eventually comes to the conclusion that the shadows had lost interest in their walls. This artwork and its corresponding story function as Raad’s urgent call for an arts infrastructure that is senstitive to the effects of violence on art, and deserving of the new architectural forms this makes possible.

Preface to the seventeenth edition, 2020

In 1975, at the beginning of the wars, most public monuments in Beirut were hastily disassembled and stored in unmarked crates. The crates were dispersed to various secure storage sites.

Thirty years later, the crates were gathered and opened in the hope of re-assembling the monuments. However, the lack of a break- down and re-assembly protocol resulted in the odd composition of new public works, one of which is on display here.

Foreword to the Arabic edition, 2019

While visiting the recently opened museum of modern Arab art in Beirut, I noticed with great surprise that most paintings on display had no shadows.

At first I was beside myself, convinced that religious zealots had destroyed the shadows. But no umbraclast came forward.

I then pondered whether the museum's walls had been painted with a white so white that shadow is cast on them.

But I suppose I should have known all along that the shadows were not destroyed nor invisible: they had simply lost interest in the walls where they were made to hang.

I decided to build new walls on which I carved shadow-like forms — magnets of sorts — in the hope they’d attract the restless shadows.

Thus far, not a single catch.

wood, paint, 244 × 122 × 11.4 cm each, unique

Another letter to the reader, 2015

Sometime in late 1914, Young Turk Minister of War Enver Pasha ordered the storage of hundreds of Iznik motifs thought to be in danger of extinction and/or to protect them from war-time damage. The motifs were crated, boxed and stored in various banks’ vaults in Istanbul. Little did anyone suspect that the motifs somehow managed to sneak out during the war, leaving behind the safety of their shields. While most government officials accused the motifs of treason and subversion, and sought to bring them before the Turkish courts-martial of 1919-1920, few realized that the motifs had actually left their containers looking for the blue, green, and red colors that had long abandoned them.

wooden crates, various dimensions

Raad’s newest series of works bridge the concerns expressed in his two ongoing art projects: The Atlas Group, and Scratching on things I could disavow. In his new monumental sculptures made of wooden transport crates and titled, I feel a great desire to meet the masses once again, Raad delves tangentially into the conservation of monuments in times of war.

Preface to the seventeenth edition, 2020

In 1975, at the beginning of the wars, most public monuments in Beirut were hastily disassembled and stored in unmarked crates. The crates were dispersed to various secure storage sites.

Thirty years later, the crates were gathered and opened in the hope of re-assembling the monuments. However, the lack of a break- down and re-assembly protocol resulted in the odd composition of new public works, one of which is on display here.

wood, paint, metal, 348 × 263 × 100 cm, unique

Similarly, Appendix 137 scrutinizes artmaking in times of war, with particular emphasis on the close relationship between Lebanese artists, militias and their uniforms.

Appendix 137, 2018

Several Lebanese artists volunteered their services during the war years and created camouflage military fatigues for the fighting militias. Their designs were catalogued in this book by Farid Sarroukh, a mediocre immodest painter who was irked at not having been asked to submit his own designs.

pigmented inkjet prints, 90.3 × 71 cm each, Ed. 5 + 2 AP

Sweet Talk: Commissions (Beirut), 1987/2019

These plates are from a book I found in a flea market in Beirut in 1994. It consisted of streetscapes of the city by an unsung Lebanese photographer, Ahmed Helou. What also drew me to the book were the hand-written inscriptions in Arabic on each spread, diary-like entries, most likely written by the book’s previous owner.

inkjet prints, 51.5 × 73.5 cm each, Ed. 5 + 2 AP

Appendix 153, 2019

These paintings were made in the 1970s by a relatively unknown painter named Suha Traboulsi. They were thought to be experiments in Abstraction, typical of Op Art experiments elsewhere at the time. Recently she confided to me that these paintings were actually inspired by photographs of the shelling of Beirut in the mid-70’s. She also gave me the photographs that inspired the paintings. They are pinned next to the color chart. She also gave me captions in Arabic to attach next to the photographs as well.

pigmented inkejt prints, 61 × 91 cm each